I SPEND EVERY Friday afternoon in a place I would never spend a night.

Sometimes, working late, I begin to hear weird and haunting sounds in the building, like low voices and small bangs. Once an intern heard the sound of chains. There is a strange air about the place, and I try never to stay after dark.

*

THE OLD JAIL in my town is a two-story red-brick building whose front and only door, when you pull it from the outside, opens into a small office. The office leads to a concrete fortress with bars on the windows. Jail cells, patented in 1874, had their lever-action doors removed so that nobody plays a bad joke. Inside the cells are metal cots.

Downstairs in the northwest corner, set in the ceiling, is a trap door made of metal, 3 feet square. It opens at the center with a lever, like a draw bridge, as if to pour out the contents of the upstairs into the cool air below. Upstairs there is no sign of a trap door. The floor has been covered in particle board, then painted gray.

This building is our local Archives.

*

I BURY MYSELF there on Friday afternoons. At my fingertips is all of American existence, and much of human existence, the extent of the crazy things humans will do. Ours, Tattnall, is one county in a nation delineated by thousands of counties, and yet, it contains all of love and hate and lust and systematic oppression and greed and obliteration. Everything is there.

My time at the Archives is spent studying story.

I talk about "story" as if everybody knows what I’m talking about. A story, I believe, is a retelling of life, an opening and a closing, a framed piece of knowing—ordered with a beginning, middle, and end. A story contains conflict and details and a sequence of actions that give shape to chaos and understanding to bafflement.

I also spend time at the Archives saving stories.

*

A FEW YEARS after I bought a dream-farm thirteen miles out of town, a woman named Ruth Anderson called. Short and white-haired, Ruth was a retired teacher, and she lived in a house a block from the library. She had been involved in everything in my new town that remotely interested me—restoring a historic hotel, getting it on the national register, running the Garden Club. She asked me to meet her at the Archives.

That day she nosed her luxury sedan right up to the door of the Old Jail. I was waiting for her on the steps. She beckoned me to her car window. "I always called this my parking space," she laughed. The sedan’s tail end stuck out in a line of traffic.

She reached over to the passenger's seat and jangled a set of keys, then handed them to me through the window. "You're going take over the Archives," she said.

"I'm sorry?"

"I've been diagnosed with Parkinson's," she said. "I need you to take over the Archives."

"I don't know anything about archives," I said. "I've only been inside once."

"You'll do fine. I wish I could stay, but I've got an appointment. Call me if you need me."

"Wait. Ms. Ruth." I said. "You can't just hand someone the key to the Archives."

"Why can't I?" she said. She actually waited for an answer.

How could Ruth Anderson hand over a key to a county building not fifty feet from the courthouse and tell someone—a transplant who once took a ten-minute look around—that they now had control over the entire historical records of a county?

Ruth was of a generation and class of women who figured out ways to beat a system that undermined female power. I've watched a number of these women operate. Their method is a faux passivity that never smacks of defiance. They never go public.

"Doesn't somebody have to approve?" I asked her.

"I do approve," she said. She backed her sedan with a screech and peeled away.

*

I HAVE PHOTOS of what the Archives looked like the day I entered. The office walls were papered with architectural drawings from a courthouse renovation fifteen years earlier.

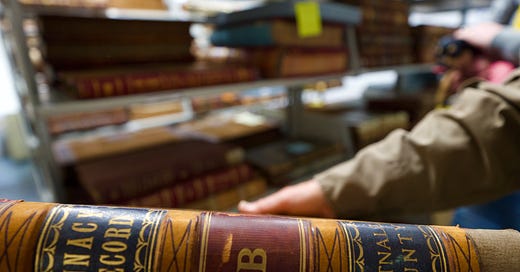

Inside the stacks, probably fifty boxes of old documents were piled on top of each other. Piles of historic record-books towered, leaning. A filing cabinet was stuffed with papers and photos, a closet filled with more mysterious boxes. An air conditioner leaked directly onto a metal shelf of old books. The place hadn't been dusted or mopped or painted in years. Roach droppings piled in corners.

The first thing was go home and try to process what had happened. Then I went back, unlocked the door with my new personal key and started to clean, untacking blueprints from the walls and drying out the books left moldy by the air conditioner and sweeping up a rat carcass from a corner and moving shelves with feng shui in mind.

*

I HAVE WATCHED, in my lifetime and from my vantage, the precipitous decline of rural life. For decades the countryside has been emptying of people. Civic clubs are aging out—granges, Garden Clubs, Lions Clubs, book groups. What's left is increasingly depauperate economically, familially, and culturally.

Even in rural places where population has remained steady, the level of education in the population has fallen, because rural places lose their best and brightest children to cities, where ideas flourish. That leaves a cognitive decline in the rural—towns with abandoned Archives, faltering libraries, remaindered books on history, little interest in the juiciness of history.

Most rural villages are suffering these poverties, losing a richness they cannot even imagine because it is buried underneath the years, locked inside moldy boxes, allergenic and headachy.

*

OUR TOWN HAS an architecturally stunning courthouse, or rather, it did. Designed by James Golucke and finished in 1902, it featured a mansard roof with an impressive clock tower at one corner. Then in the early 60s a stellarly ignorant bunch of commissioners voted to remove the third floor and the tower, and now our stately old longleaf pine courthouse looks like a box.

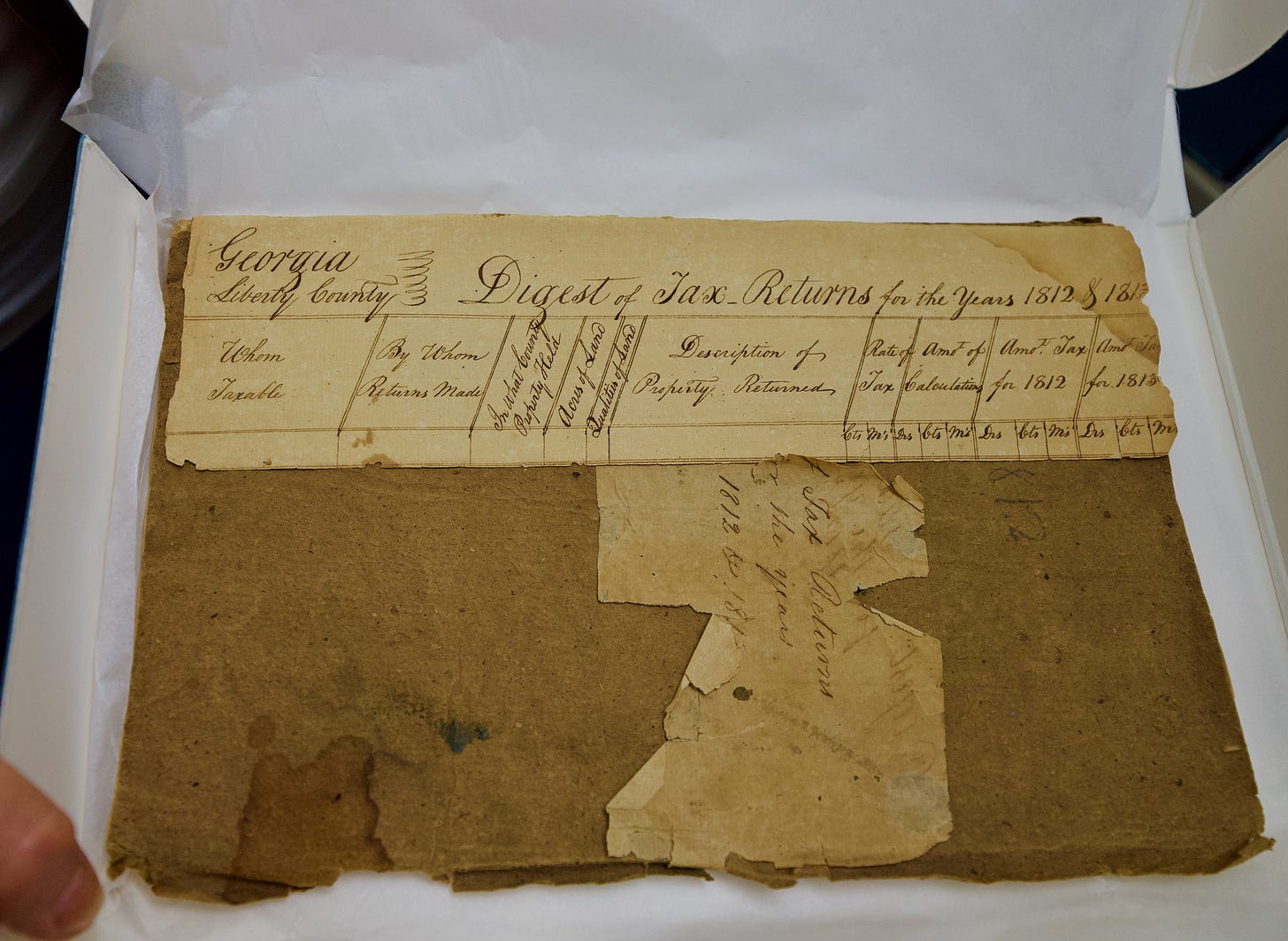

It was on the upper floor that county officials had been storing old documents. Courthouses were notorious for burning to the ground, but this one never did, and the documents reached back to 1801, the founding of the county, thirteen years after Georgia became the 4th state in the union.

During the roof removal, workers were found tossing all that valuable historic material into dumpsters. An alarm went up and what followed was a flurry of activity to organize an official Archives—a committee received permission to take over the Old Jail, to get help from the Georgia Archives in filing documents, to write a grant to catalog the volumes.

A lot got done.

But, as happens with many projects, people lost interest, got dejected by the amount of work that such an undertaking required, and turned their attention elsewhere. Ruth kept things going as best she could. She unlocked the place when a researcher wanted to poke around.

*

ONE DAY I found a document dated 1790. I reeled. I read the date again. It was a promissory note, someone agreeing to pay someone else a few hundred dollars.

Every hour that I spent in the Archives, handling old material, a strange thing began to happen. The past contracted. Before, 1790 seemed ancient history. The longer I sat with documents, the more my experience of time changed, until finally a date such as 1790 seemed like yesterday.

How do I say this? We experience time strangely. As children, old age seems impossibly far away. Because death is so final, anyone who is dead is history, and people have been dying for thousands of years, as long as humans have existed, and thus someone who died any moment before the present moment is long dead, and therefore becomes jumbled in the chaos and darkness of the past and also the cloudiness of culture.

The present and the future are highlighted, bright yellow.

The past is gray and fading.

But I began to see myself as I would become, another character in a long saga of interesting characters, part of the mysterious and illustrative past. Whereas history had seemed stories about one-dimensional characters in a time so remote it could have been prehistory or it could have been imagination, history was now. It was me.

I have no training, but in that epiphany—the awareness of my dot on a long, long timeline—I became a historian.

I set up a board of directors, people with years of experience and skill. For many years I have met every Friday afternoon with a group of volunteers, slowly working our way through box after unsorted box of documents, unfolding them and sliding them into archival folders and labeling them and creating a digital genealogical index that now includes 55,000 entries.

We began to open to the public on Friday afternoons.

The most valuable documents are two or three that contain the signature of George Walton, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Though he resided in Augusta, as a Superior Court judge he rode a circuit and those travels brought him to my town on court days. His signature on the documents looks exactly as it does on the Declaration.

I have become the kind of person who thinks, When the Archives closes, there's nothing to do in Paris.

*

IN SOME CASES, the stories at the Archives uphold the dominant narratives of our time, and in some cases they bust up these narratives. That fascinates me, what sticks and what does not.

These narratives were broken for me at the Archives:

That divorce is a modern phenomenon. I see divorce cases back into the early 1800s.

That people lost their farms during the years we know as the Depression. I know now that people were losing their farms long before the 1920s, in debt because of guano bills, in debt because of mules, in debt because their eyes shined for an automobile.

That women throughout the settling of America were mostly without agency. But I could tell you the story of America Martin, who ran a boarding house in Cobbtown, fathering multiple children by multiple men, accused of operating a "lewd house;" and of numerous women in the 19th century who ran a husband's business after his death. Yes, there are stories of rape and bastardy and domestic violence, but there are also stories of female courage and ambition and intellect.

That the word "fuck" is new to our vocabulary, that surely it doesn't appear in a document in the early 1800s.

That if Jewish culture is dead, it never existed. But Jewish culture was thriving into the early 1900s in rural southern Georgia. We have the documents to prove that a rich Jewish culture existed and then disappeared, the records full of Jewish names, Rosenheimer and Walpert and Lipsitz, now almost 100 percent gone.

*

THE RECORDS CONCERNING race are the ones that most fascinate me, because the untenable story of the present moment is grounded in the untenable story of the past.

Bryan Stevenson of the Memorial for Peace & Justice in Montgomery, Alabama said, in thinking of the truth and reconciliation of Germany and South Africa, “Truth and reconciliation takes both. Reconciliation is not possible without truth.” And truth is a multi-layered, incredibly complicated, many-storied thing.

In 1805 Lorene Arnold petitioned the court for a certain negro boy named Samson, of the value of 400.00, sold to John Swilley, who refuses to pay.

In 1822 Ann Farmer was interrogated regarding a sale of enslaved persons. To a question she answered, “I do know that Thomas Colding purchased the wench Rachel and her child about that time of my husband. It was paid with a negro man named Paddy. He had owned Paddy for a number of years but I can't tell how long.”

Also in 1822, Abram, a “negro man slave,” as the record reads, was accused of the offense of burglary, for sneaking into the home of Allen Johnson in the middle of the night and stealing a shott-gun, powder-horn and shott-pouch.

One of the most fascinating documents was the trial of Shadrack. "For that the said Shadrack, a 'negro' man slave, and then and there the property of one Joseph F. McGovern, on the tenth day of October in the year of our Lord 1854, in the county of Tatnall aforesaid, with force and arms, then and there, in and upon a certain negro man slave named Will there and then the property of one Henry Strickland of said county of Tatnall, in the peace of God and said state, then and there being unlawfully, willfully, feloniously and of his malice aforethought did make an assault: and the said slave Shadrack with a certain pole, of the value of twelve cents, which he, the said Shadrack in that his hands then and there had and held, him, the said slave Will in and upon the left side of the head immediately above the left ear of him, said Will ….did strike and beat, giving to the said Will then and there, with the pole aforesaid in and upon the left side of the head….one mortal wound of the breadth of six inches and the depth of three inches and one mortal bruise….” The document goes on to say that "Shadrack did kill and murder contrary to the laws of said state, the good order and peace and dignity thereof." This was 1854. Seven years later Will's owner, Henry Strickland, would represent Tattnall at the Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 where he would vote not to secede, but like so many others, would cave, to the disappointment of his constituents back home, and to the huge disappointment and profound grief of me, almost 170 years later. Shadrack was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter. The question was what to do with him. If enslaved people were property, one man's property had destroyed another man's property. And the verdict: "Whereupon it is considered and adopted by the court that you ‘Shadrack,’ a negro man slave, be taken hence into the common jail of Liberty County and on the third day of November next that you be brought back and that you be branded on your cheek with the letter ‘M.’ Then that punishment is crossed out and replaced with…."you be brought back and given on your bare back 39 lashes between the hours of 10 a.m. and two p.m. and then be branded on your cheek." His owner has to pay court costs, about $10. But why, if in 1854 we thought of slaves as property, was Shadrack even tried at all? Why wasn't McGovern simply forced to repay Strickland for the cost of Will? That's because a cognitive dissonance existed in our society and we knew it existed and we chose to ignore it and we choose to ignore it still.

In 1864 the Inferior Court bought corn for soldier’s families, 4 bushels of corn to Mrs. J.F. Dubberly at $3/bushel for $12.00.

On May 13, 1865 John Daniel petitioned the Superior Court for repayment, a schedule of property captured from him by the Confederate Army, "to wit two horses given in at $1000 each makes $2000 and one negro man escaped to the enemy given in at $4,000 makes $6,000, for which I have paid the tax on for the year 1864.”

Also, there is a lovely book called "Colored Marriages: 1866-1871." At war's end, marriage was a civil right at last afforded to former enslaved people and free people of color.

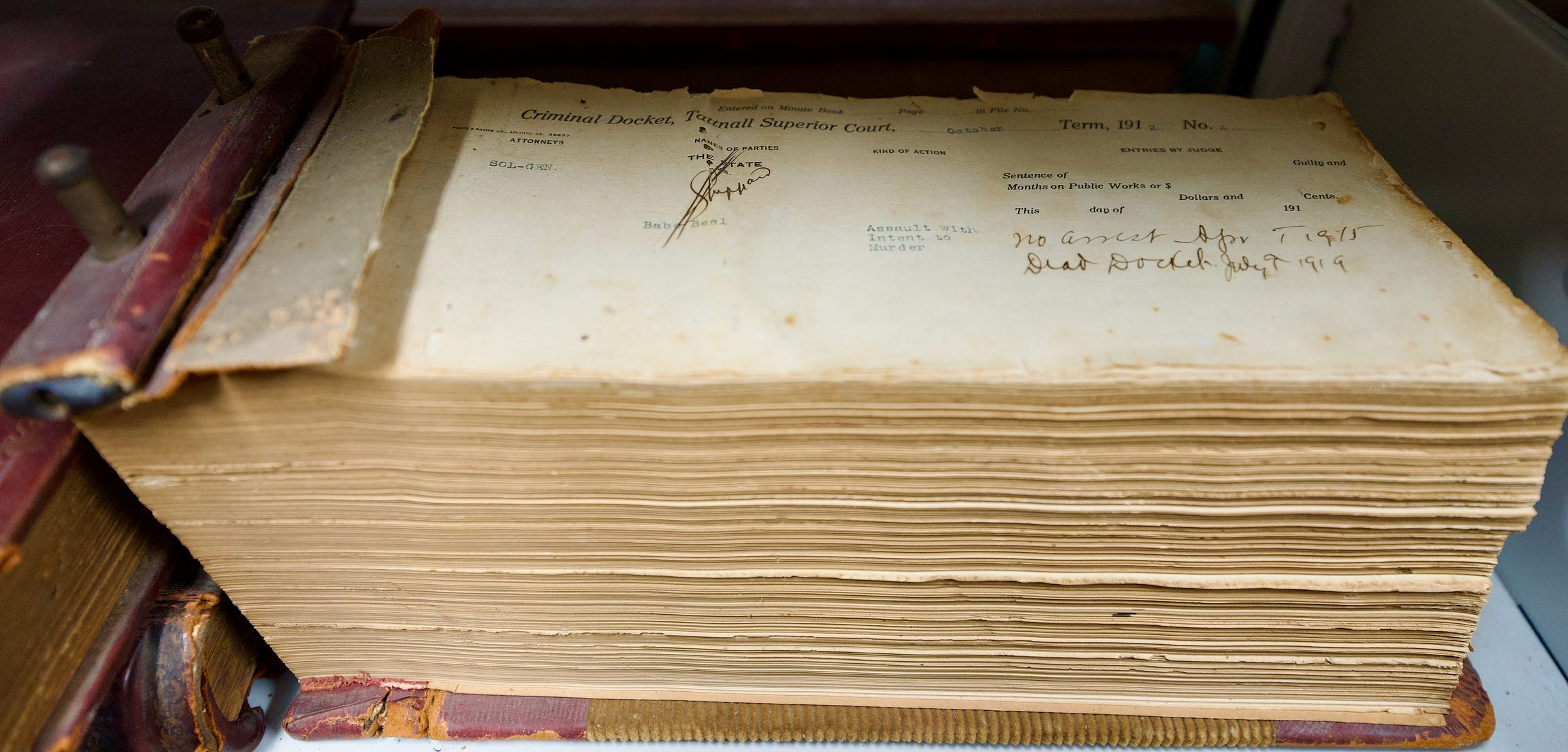

In the 1900s and 10s, through the 20s and 30s, records began to appear where the punishment became the "chain gang." The most minor infractions would send someone off to work in a labor camp for months. Someone, of course, had to report the offense. I see the same names, over and over, of the men who were turning in so-called offenders. What kind of kickback were they getting? Judge E.C. Collins sent hundreds of people—men and women, black and white, usually destitute—to the chain gang. Part of what's important in studying these old stories is deciding to look at the evidence and think for yourself. No one can think that three months of hard labor is just punishment for "wandering about in idle pleasure."

In the 1960s, when Martin Luther King was imprisoned in Reidsville, correspondence and court records from the Warden show that Georgia State Prison was preparing for riots with the arrival of Dr. King. They were making sure that anyone protesting could be summarily arrested.

*

AS A NATURE writer, I am very interested in what can be learned through primary records of local history: place-names, the roles our rivers played in daily life, common names for land forms, illegal interactions in nature (dynamiting for fish in the river, for example.) There’s a world of information in the spooky Old Jail.

*

IN GOING THROUGH the astounding records of my local Archives, I have attempted to study the material enough to see patterns and trends, like a historian.

Instead, time after time, what I see are stories of individuals who either prove or disprove a pattern already established. But without these stories history would have happened somewhere else. What I have learned, then, is the universality of the human condition, and out of this universality, deviation.

It's all there, bastardy and bestiality, rape and murder, adultery and fornication, slavery and indentured orphans, Jim Crow and lynchings, speeding and debt, cheating and swindling, larceny from the house, larceny from the smokehouse, larceny from the store; and also love, romance, friendship, acts of kindness, acts of greatness, acts of generosity.

Mostly, going through the records, I am looking for acts of resistance, the people who stepped right when others were stepping left.

There are deeper meanings to what I find.

That some of our stories uphold justice and some uphold injustice.

That truth is different for different people.

That one primary document is only the beginning of a story that is as multi-layered and complicated as humans themselves.

That many of the stories didn't get told. We get the warden's story and we get some of Dr. King's story, for example, but we have to keep looking to get the story of the local black shopkeeper and the people of color who marched the nine miles from town to the prison to protest Dr. King’s imprisonment and Jim Crow rule in general.

*

I’M TRYING TO build up my courage to actually spend a night at the Archives.

One of these nights I hope to try it. I’ll make it into a fundraiser, and you can pay me for every hour I spend lying in a cell staring at a trap door in the ceiling, listening to the voices of the people trying to set the records straight.

*

HISTORY HAD BEEN a thing that happened somewhere else, in England or in Boston, but now, once I began to spend time at the Archives, history was a thing that had happened here, locally, to this place, to these people who were my people. It was also a thing that was happening, in the present, to me.

If you learn history from the outside in, you are forever trying to reconcile generalizations with the specific. I think it’s important to also learn history from the inside out.

The entire history of humankind can be found in our little Archives.

All the past becomes an investigation, and the Archives is full of evidence. This is important because 1491 was yesterday. Hopefully then we might live today and make decisions today knowing what we have learned, and that would give us the marvelous chance to do things differently from now on.

What an amazing story and opportunity for you! Archives are priceless.

Wow! Just wow.