Exploration 1 | Journey in Place | Claim Your Place

We can no longer ignore place.

Welcome

Welcome, dear one, to our year-long study of place. Your place needs you desperately. It’s glad you’re here, all the other place-lovers are glad you’re here, and I’m glad. A thousand welcomes to you.

Tiny Essay

In little more than one hundred years most of us have become placeless people.

We live in places, we visit them, and we travel between them, but they rarely have deeper significance. Our ties are financial, or familial, or medical. Sometimes we stay in a place simply because we find ourselves there.

We mostly don’t know

when there’s frost

what a certain arrangement of clouds mean

how the wild animals and plants interact

what’s native or not native

what can heal us

what can feed us.

I say this without judgement. We’ve been asked to ignore place in order to get by. Capitalism needs us to be placeless, homeless people. It needs a workforce, and in a global marketplace, it needs us to become global.

Yet we are biological creatures, absolutely dependent on the earth for survival. We can’t get by without nature.

And how far we are from it, most of us.

Thousands of generations of folks who came before us never knew cell phones, global positioning systems, and computer apps. They knew cycles of seasons, of suns, of moons, of weather, of tides, of migrations, of all things that connect us to the earth.

Relationship to place has been a central theme of my life, a consuming passion, a knotted ball of yarn I have spent years attempting to untangle. I have come to believe that we lose an essential part of our selves when we lose our engagement with place.

This course is about connection to place, which I call place-knowing. (I want to call it place-making like everybody else, but that gives power to us as makers, and we are not place-makers. We are place-lovers.) It’s about being part of the cycles, being in cycle, being cyclical. It’s about listening.

Get ready. We’re going to start spinning with the Earth as it turns every 24 hours on its axis, spinning as it makes its annual revolution around the sun, while the sun spins around our galaxy, the Milky Way, which moves through the universe. Spinning dizzily, we watch the moon as it spins around the spinning Earth.

Go outside, spread your arms wide, feel yourself spinning, and say hello to your place.

Feet on the Ground: Find a Power Spot

Apparently this is a common exercise for nature retreats and outdoor schools. I heard about it first from the nature writer John Tallmadge, from his essay in the book Into the Field: A Guide to Locally Focused Teaching. He called it a “Power Spot.” Author Sharon Blackie, in her book The Enchanted Life calls it “The Sit Spot.”

Wander about your place until you find a spot that draws you. “Ideally, it should be close to where you live;” writes Blackie, “it should be a place where you can observe nature; and it should be a place where you feel safe and can remain alone and undisturbed for a while.” Take a deep breath. Breathe. Listen. Sit there for as long as you can listening, observing, and sensing. Your journal would love a quick entry about this experience in your Power Spot.

You will return to this very spot multiple times throughout the year.

The aim is simply to notice. To settle down, focus your thoughts on the present moment and notice the flow of life around you.

Sharon Blackie

Mobility

I know (because they’ve told me) that some folks who are Journeying in Place experience mobility issues. If at all possible to get outside, do. A spot on your porch or deck or balcony is fine. If you can’t get outside, position yourself by an open window.

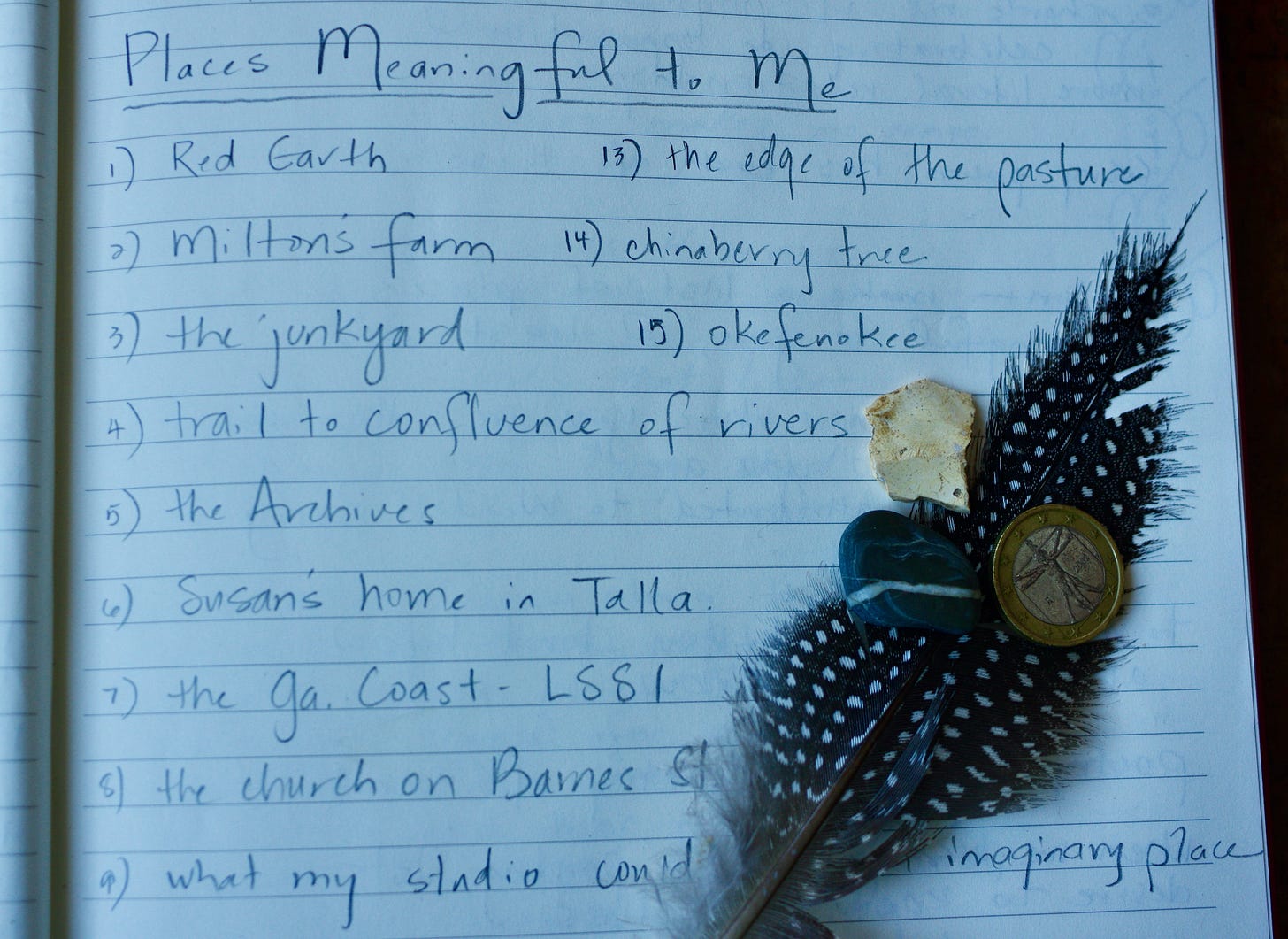

Make a List

I’d love for you to start a list in your journal of places that have mattered to you. Write down at least 20 meaningful places.

They can be places

that are particular (a room)

that are general (a region)

that no longer exist

that have changed

that have not changed

where you found joy

that make you sad when you think of them

that you return to

that you only saw once.

(Thanks to the poet Denton Loving for telling me about this exercise at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro a few months ago.)

Claim Your Place

This week we’re going to claim the major place we’ll be exploring. To do that, we need to know exactly what we personally mean by “my place.” For the sake of our course of study in place-knowing, what do you consider your place?

Be as specific as you can. Is it your city lot? Your suburban backyard? Your farm? Your neighborhood? Your region?

I’d love to get some idea of the scale you’re using to identify your place.

Writing Prompt

Please describe the place that owns you.

I invite you to post all or some of this in the comments.

Pre-Course Survey

If you’d like to take the pre-course survey—and take it again at the end of the year to see if there’s a difference—here’s the link.

Housekeeping

I can’t find where Substack collects mailing addresses, and I will need yours at the end of 2024 in order to mail you the book, Journey in Place. If you haven’t sent me your address already, please do, by direct message.

Further Reading

The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday, by Sharon Blackie (Her exercise called “The Sit Spot” can be found on page 57.)

I will soon be posting a bibliography for JOURNEY IN PLACE, and I will be adding to it throughout the year.

Do Not Despair

Some of you are worried about your performance and have written me about it. If this exploration feels like a lot, please read this reminder.

1) All of these explorations are optional.

2) It’s okay to do none of these.

3) Past explorations will continue to be available, so you can return anytime to one.

4) You have the rest of your life to explore.

5) These first explorations are more consuming as we get set up. Things will settle down.

Two Matters of Safety

Lyme Disease

Ticks across the U.S. carry diseases--Lyme, alpha gal, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and more. These are serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses that can be contracted

anywhere in the U.S.

at any time of year

in places you thought ticks did not exist

by ticks of all sizes.

The science behind contraction of Lyme is not complete. Until it is, please act with extreme caution. Any foray into nature is potentially dangerous.

The length of time the tick is latched on you should not be a factor in making a decision to seek treatment for a tick bite.

The presence of a bull’s-eye rash should NOT be a factor in determining to seek treatment. Tick-borne diseases can be contracted without the presence of this rash.

Prevention is Key

Wearing light-colored clothing helps you see ticks.

Tucking your pants in your socks keeps the tick climbing upward and makes it more visible.

Double-sided tape is available for socks.

Before going out in nature, I HIGHLY recommend spraying outerwear with heavy-duty (DEET) insect repellent.

boots

socks

leggings

pants

top of hat

back of jacket

I don’t recommend spraying these chemicals on your skin or on thin clothing that touches your skin.

For extra precaution, avoid heavily overgrown areas and narrow trails with lots of brush. It might be wise to sit on a rock or on a blanket that has been sprayed with insect repellent and not sit directly on the ground. Bring a plastic bag for storing the blanket after use.

Finally, please do not let ticks stop you from connecting with your home, the earth. Go out anyway, listen to the hurting but still healing earth. Resist the temptation to give in to fear.

Physical Safety

Your physical safety is of utmost importance to me. Go into nature with a partner or let someone close to you know when you’re going. Arm yourself with bear spray, if necessary for your comfort and relaxation. Be aware of your surroundings and where you step. If you can’t recognize poison ivy, look it up.

If you’re new to exploring in the wild, consult with someone more knowledgeable.

Finally, please do not let your fears keep you from making the deepest connection of your life.

Next Week

We’re going to look at Bioregions.

Happy Trails

Thank you so much for being along on this journey. The earth desperately needs you. She is calling out for you. She welcomes your presence, your attention, and most of all your love.

The place I belong to is a one-mile by one-mile square of sorts, bordered by two graveled roads. It’s part of a rural area that is 15 miles outside of a small village that has no traffic lights. My elevation is 2400 feet - a gradual climb in the foothills of the Cascade Range of southern Washington State that I refer to as "30 minutes from everywhere."

This place represents much change and growth in so many aspects of my life. I abandoned a career and suburban lifestyle to move here, to change my lifestyle after living in urban and suburban settings for 50 years. My friends called it my mid-life crisis - I agreed 100%. I was 50 and my crisis was a life of discontent, boredom, and a brewing hopelessness. I had a vision of living closer to nature, a return to four distinct seasons, a connection to the small village down the hill, and days spent outside.

I was widowed unexpectedly, in one night, in my second year here. My grief was complicated and at times profound. City friends urged me to move back to the city -to come home - I couldn’t possibly live here by myself. But it was too late; my heart was now part of this place and it had laid claim to me.

It could be the towering Douglas firs, who offer some protection from this region’s infamous winds. It might be the ravens who fly over and greet me with a loud caw as I work in my garden. Or the arrival of the swallows, who cause me to stop and look up to watch them eat on the fly. My relationship with the gawky and prolific elderberry shrubs is key to my winter wellness, wildcrafting their spring flowers and late summer berries for remedies. Those not-native-but-always-welcome wild turkeys that migrate each day from my neighbors on the left, through my front yard to my neighbors on the right, and then back, sometimes make me flinch at their seemingly unkind pecking behavior. And the light! The 14 hours of light of the northern spring, the hot intense overhead sun of the summer that forces me into the garden at dawn, and my favorite, the diffused low light of autumn highlight the pasture dying grasses.

For 15 years, I have walked the two roads almost daily, always accompanied by my beloved dogs, and occasionally with my wonderful neighbors. Despite our introverted natures, we have developed a sense of community and rely on each other for those moments in life when we need community.

This morning, before the light arrived, coyotes were yipping and howling in the woods that exist between my place and my neighbor’s. My cat, once a feral kitten, ran for cover in one of the bedrooms (I thoroughly enjoyed that fear-based reaction as he is the bully in the house). My dog, Beau, jumped off the comfortable couch, went to the window, and joined in the howling. I listened with a smile on my face and pondered how that ancient instinct to howl with a pack was never domesticated out of existence. A moment of wildness.

Like Beau and the coyotes, I experience a sense of wild contentment, living in the space between wildness and domestication.

I live amidst sprawl, in a two-bedroom, two-bath apartment with what the management company generously calls a “deck,” in a pre-fab apartment complex on the other side of the interstate from Kroger, Walmart, and Macon’s AMC movie theater. My daily walks allow me to see the hidden ecosystem that surrounds and survives despite all of the human activity.

My walks take me on the sidewalk on one side of Zebulon, past the Chevron and auto parts store, to where the sidewalk ends at the “Jesus Saves” sign that marks the entrance to the Rock Springs Church, thrift store, and mission. There’s a drainage ditch there where the first butterflies appear each spring among the rocky grass.

I cross the street at the light and walk down the sidewalk on the opposite side of the road, past a couple of abandoned houses to where the trees begin. Pear trees, privet, and wisteria are prominent among the tall pines. I walk to where a chain stretches across a sort of entrance to the woods. I’ve never gone in there–having seen other small glades in the neighborhood where people had set up small camps, I’m afraid of disturbing a place that isn’t mine.

I turn then, retrace my steps, and keep going past the Shell Station, the pizza place, the new liquor store. The storefront by the on-ramp that has sat empty for several years just opened as a used car lot. Beyond that is the overpass, and one of my favorite secret bits of nature. I have come to know the ecosystem at the 475 overpass over the past seven years that I’ve lived here, its changing vegetation over the course of a year. I know early spring when the purple morning glory vines appear. There’s a stand of trees where I’ve seen deer more than once. There’s a gully where a flock of purple vervain grows each spring so brilliantly that I’m often reminded of Alice Walker’s warning that it’s a sin to pass a field of purple flowers without giving thanks.

When I return home, I often go out on my small “deck” where I try to cultivate a sort of ecosystem in a crowded container garden and bird feeders. I have two small shelves and a table with pots of plants, many of which have stories I can tell. There are two pots of night-blooming cereus: one was rooted by my cousin Debra in Sylva, North Carolina, and one was rooted by my friend Erin in Athens, Georgia. I first saw night-blooming cereus at Eudora Welty’s house in Jackson, Mississippi, and I’ve been enchanted by it ever since. In the window are pots of pothos that I rooted from a plant of Mamaw’s, along with several orchids that I inherited from my friend Jeanne when she moved away from Macon to Oregon.

I keep a few field guides on the table by the door to the deck, where I sit and sometimes work, sometimes look out the window at my garden and the trees beyond. The first birds I saw here were a pair of cardinals, male and female; a friend told me that cardinals are a good omen, as they mate for life. I then identified an Eastern towhee that was banging against the glass in the door; I had been dreaming I was in Wuthering Heights, so I call the towhee “Cathy.” I was enchanted by the Carolina wren, whose eyeliner reminded me of the actress Divine; towhees are now my “little divine birds.”

These hidden pockets of nature in my neighborhood are what I plan to write about.