When I was young, I decided that I was going to have an adventurous life, and so far, that has come true. The craziest things seem to happen.

Yesterday, for example, I was coming back from the mailbox when a 4-foot rattlesnake crossed the dirt road. It crossed under the hogwire fence, headed straight toward our house. I grabbed a stout 7-foot limb that had fallen, got between the snake and the house, and began to plunge the end of the stick downward against the ground. I was hoping to make elephant-size vibrations and turn the snake back.

The snake did not want to change course, so sometimes I’d have to gently push against him with my long stick. There’s no way that I’m going to hurt or kill a snake, not on purpose, but a rattler that large is an unsafe visitor. For a few minutes, I was engaged in a heated and serious battle, and finally I guess I scared the snake with my Maori stick-fighting methods. He stopped just outside the fence. “Not good enough,” I said, and kept beating the ground. I chased him all the way back into the woods across the road.

My early-life decision to choose a gripping narrative rather than a placid one has not been without consequences, however.

Recently my friend Jeff Dwyer, who is my children’s book agent although we’ve never been able to sell one, sent me a link to a spirited and radical conversation between journalist Nina Burleigh and commentator Greg Olear, on his podcast “Prevail.” Speaking in old-school terms, Nina says the difference between women and men is that women are impregnable. Impregnable.

That got me thinking about the one birth I’ve ever experienced, which I could have done more neatly and safely, instead of finding myself in a cabin without electricity forty miles from the nearest hospital with a 75-year-old granny midwife.

I wrote my birth story, and I’m sharing it with you here. I’m warning you again, if you’re not comfortable with body parts and some blood, don’t read this. Getting the story on paper gave me a feeling of incredible lightness, as if I were freed from something that had gripped me, and I could finally see that night as the transformative experience it was. I could see myself not as a victim but as a clear-eyed goddess. (Well...)

So I’m doing a birth-story writing workshop. It’s 2.5 hours early on the Saturday morning of Labor Day. I set it up for 8 am Eastern Time, but there was interest from the West Coast from people who didn’t want to get up at 5 am, so I added a second workshop, at 8 am Pacific Time (11 Eastern). There’s more information on my website. You can sign up for either time, no matter where you live. All are welcome, as long as you have attended or assisted at a birth and want to tell the story. Sign up here or here.

There are five scholarships for single parents who are experiencing financial hardships. Be in touch and I’ll tell you what to do. And I have a special code for anyone who has taken a writing workshop with me in the past.

You’ll find my birth story below.

Thanks to Kate Van Cantfort for the workshop graphic.

Light Will Drive Out Darkness

In a small cabin in the woods of north Florida, at night, a woman was giving birth. She was alone. The year was 1988. The woman was me.

Heavily pregnant, I’d been washing dishes at the kitchen sink when I felt a contraction that seemed different than the small ones I’d been having. My due date had come and gone three weeks earlier, and the days had crept along. Now this contraction wrung my body as if I were a rag.

Before long there was a second contraction. I dried my hands, went to a window, and pressed my face against its pane, peering out into the darkness. I turned, lifted a kerosene lamp, and climbed carefully to the loft. Beside the bed was a watch. I retrieved it and climbed back down the ladder. When another contraction came, the watch said 10:07. Another came at 10:15, eight minutes later.

Could this be it? I thought.

I lived with my handsome, blue-eyed husband in a cabin we were building ourselves. I hadn’t known Mose long when I’d found out I was pregnant. We rushed to get married, a beautiful outdoor affair up in the pasture; and we scurried to begin building a homestead for our little family on land Mose owned. The cabin was lovely, situated at the edge of woods, under a tall beech tree. French doors opened onto a screened porch.

I went out on the porch and peered into the dark woods, then toward the pasture. It was mid-May and the time people call blackberry winter. A front had passed and the temperature had lowered to the forties at the exact time of year that blackberry blooms were strung like pearls along thorny necklaces.

A contraction began and I went inside and held the watch to the lamp. Seven minutes had passed. I got the broom and swept the pine floor. I shook the rugs out the door and built a little fire in the woodstove. By the time the fire was going, the contractions were timing at six minutes.

I knelt in front of the little fire wondering what to do. Pregnancy had been difficult. Mose and I were finding that we were less compatible than we hoped. Although we shared a lot in common, including a gravitation toward anything counter-cultural and a love of nature, we had been under the extraordinary stress of having to make many major decisions too quickly. Should we marry? Should we make it legal? Should we rent an apartment? Should we build a home? Should I quit my job? Should we do a home-birth?

As the months had passed we began to argue more and more. Then when the baby’s due date came and went, our lives got even more stressful. Should we wait it out? Should we induce labor? Was home-birth still a choice?

More and more we were on opposite sides of a fence.

In fact, we had argued at supper. Frustrated, Mose fled the house in a huff, slamming the door. I had no idea where he was. He had left on foot and probably had gone to a neighbor’s house to visit. Or he might be far down the dark road, walking and thinking.

Now I had more decisions to make. Was I in labor? Were the contractions real or was I an alarmist? Should I begin calling the neighbors, looking for Mose?

The decision not to look for Mose came quickly. I didn’t want the neighbors wondering why Mose was not at home with his hugely pregnant (and impossible) wife. That was irrational, I know, the first of many irrational moments that would come in the next couple of hours.

I wasn’t sure about labor. Just in case it was happening I filled a pot with water and put it on the stove. I brought out a bundle of sheets and scissors that Mose and I had wrapped in aluminium foil and baked in the oven.

The contractions were clocking at six minutes. I climbed the ladder again, lantern in hand, lugging myself heavily upward, and sat with the books that were full of pictures of big-bellied women, and also that were full of me although I could not find myself anywhere in them. Where was the woman hunched in the loft of a little cabin in the woods of north Florida, alone in golden firelight, surrounded by darkness?

The next contraction didn’t wait for six minutes. It came in five.

If the contractions are regular, you’re in labor, one book said. Mine weren’t regular. They were getting closer together. That’s not regular. If your water breaks, you’re in labor. You’ll know when your water breaks. My water had not broken. Length of labor differs. For first babies, it’s longer, sometimes a few days. I had time, then. The first baby takes longer.

Another contraction came. Five minutes.

A magnolia blossom wide as a dinner plate was hanging out of a jar of water. My best friend Arne had been bringing magnolia blossoms. He was a dark-bearded Jewish man whose mother watched all the Holocaust specials on television when he was growing up, looking for surviving family. Each enormous magnolia stayed smooth, ivory, and fragrant a couple of days, then it began to wither, stain brown, and drop its stamen. Its petals loosed like sails until only a fat hard calyx remained stuck in a vase. Just the day before Arne had brought a replacement.

Another contraction hit. This one was more concerning, because only four minutes had passed. I hunkered beside the books, the watch sweaty in my palm. Labor can last a few days. You’ll know when the water breaks. Sometimes there’s a lot of water. You need a support system on call.

I kept thinking of how many women had squatted, birthed a baby, and kept working or walking or whatever it was they were doing. Surely I could be one of those women.

In fact, when I was first pregnant I’d had this kind of birth dream. In the dream Mose had gone to town for supplies. I had got up to pee and felt my belly. The baby’s head was very low and moving; I felt a big roundness in my vagina and I knew I was in labor. Suddenly my water gushed out, bringing the baby in such a rush that it landed halfway under the bed. The baby was tiny. I scrambled for it and when I picked it up I saw it was a boy.

It’s weird how much of our dreams come true.

Any minute now I thought I’d hear Mose coming home and I would say to him, The time has come. He had been gone a couple of hours now, and anytime he would be coming home.

Eleven o’clock arrived. Three minutes. The dark deepened, three minutes, and within me a baby began to move toward a weak sphere of wavering light. Three minutes.

Everything changed then. I have never felt such a cataclysm. My body was the earth itself cracking, a canyon opening in bedrock. To have my baby, I would have to split boulders. I would have to move mountains.

The books had said, Breathe the pain away. Rest between contractions. I knew I shouldn’t pay attention to the pains. I should ignore them. And I tried. I really tried. But the contractions were hammers, beating down a wall. They were a bad storm. They were the waves of a tsunami throwing me backwards until finally they knocked me down. I felt myself being pulled into the ocean. I couldn’t catch my breath. I was drowning.

I can’t do this, I thought. If this is going to take hours, maybe days, I am not going to be able to survive.

The nearest hospital was 17 miles away in the town of Quincy, and it didn’t deliver babies. Tallahassee’s hospital was forty miles away. I had been wrong about having a baby at home. But now, what was there to do? I couldn’t drive myself anywhere.

The attic ceiling, recently finished with sheetrock, had been painted the beautiful peach of sunrise. The east wall was fashioned completely of windows. Underneath those windows lay mine and Mose’s bed. Only in the very pitch of the roof was the ceiling higher than my head, and when a contraction came—and they came quickly now—I pressed my hands upward, torquing my head against the ceiling.

Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God, I prayed. How am I going to stop this pain? There is no way to stop it. I need help. Oh my God, my God.

I realized then that I would die.

Far below, miles away, I heard a shuffle at the door, which I had not latched. For a minute I imagined a panther coming up out of the woods for me. I heard the door open. Footsteps quietly crossed the pine threshold of the French doors. I recognized them. I learned later that this was midnight.

“Mose,” I gasped. “I think I’m in labor.” His boots made more noises. The ladder creaked. Upstairs, the loft was dim and I saw Mose appear, thin, sandy-haired, a familiar stranger.

“Are you sure?” he said.

“Yes,” I said.

“Did your water break?”

“No.”

“How do you know, then?”

“Contractions,” I whispered.

“Are they regular?”

“Yes.”

“How close?” A contraction hit and I went down to my knees.

“They started out eight,” I panted. “Now I don’t know. Close. Oh my God. Oh.”

“You think I should call everybody now?” he said.

“You should help me,” I said. I began to sob. “I can’t do this. I thought I could but I can’t.”

“I think this is it,” he said. “I’m going to call people. Hang on.”

“Help me, help me, help me,” I chanted under my breath. “Help me. Help me.” Help me was my useless mantra.

Far away I heard Mose speak, then I heard the phone hang up. I heard him speaking again. I could hear names—Stuart and Charity and Santo and Arne and Maura. All this I heard from a far distance.

Afterwards Mose called up to me, something about sheets. He came upstairs and wanted me to come down, to navigate the wide-runged ladder, to come to the futon he had prepared with the sheets we had wrapped in aluminium foil and baked.

I wanted to do things right. I wanted a sweet, peaceful birth. I wanted to live in harmony with Mose, and create a sweet and loving family with him. But I knew even then that would never be.

I navigated the ladder to the futon and lost myself.

I want to say here that I believe birth can be calm and even placid. I believed that then, and I believe it now. Although the birth of my child is the only one I have experienced, I know that every birth is different. Some are fast, some slow. Some end in cab deliveries, some in cesarean. Some take minutes, some take days. They are all memorable, life-changing. They are powerful because they are the time a woman is most vulnerable. People lose control. People say crazy things that later they laugh at. Or not. People change. They change permanently. They lose something and they gain something else. What they gain is priceless. Nothing compares.

I know all that now.

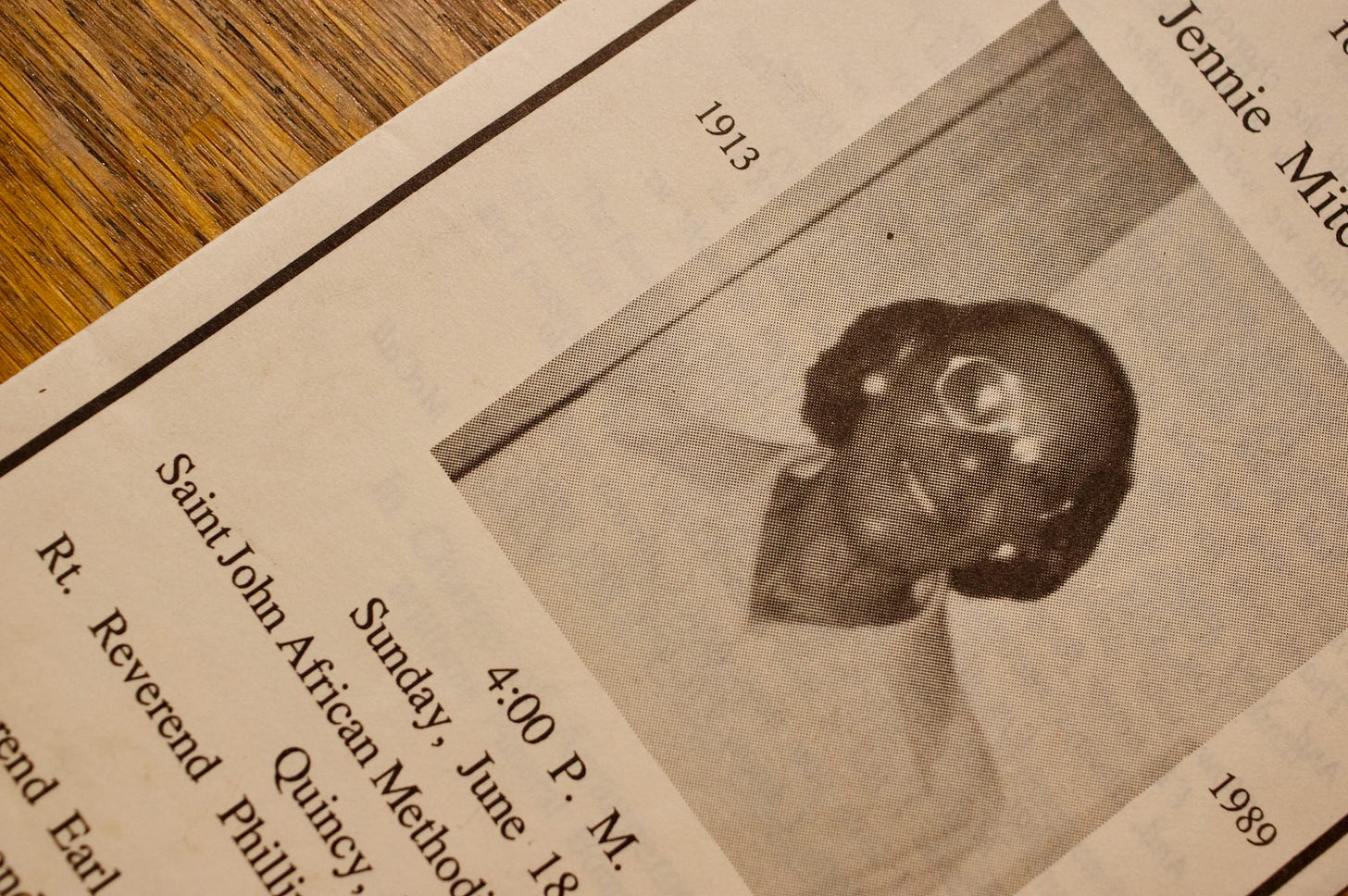

At some point I was aware that Arne arrived with Maura, a thin blond friend in midwifery training who carried her sleeping baby, a few months old. I smelled coffee. If someone put music on our battery-powered stereo, or lit special candles, I don’t remember. Charity (dark-haired, ever hopeful) came through the door with the midwife. We had been unable to find a new-age midwife willing to make the drive from Tallahassee, and finally a granny midwife had agreed to attend. We had only visited with her once.

Now she was here, with a light-blue rag tied around her head. I felt a momentary relief that was lost in a tidal wave.

I screamed. When the pain began to slide back into the horrible ocean, I heard someone speak to me.

“Shut your mouth,” a woman’s voice said. “Ain’t no need to be yelling like that. You’re acting like a crazy woman.” I raised up. Jennie, the midwife, was standing some distance away. I barely had a moment to rest before the ocean rose again.

“What you doing sitting up?” she said. “I ain’t never seen a woman trying to have a baby sitting up.”

No one could rescue me. In fact, no one would even help me. I was screaming. Charity grabbed me, her face level with mine.

“Look at me,” she said sternly. “Look at me. This is not going to work. You are out of your mind.”

I knocked her away, but she tackled me and pinned me down.

Oh my God, I can’t breathe. Another one is coming.

“You are not going to be able to have a baby like this,” Charity said. “You have to get on top of the pain. Listen to me. Focus.”

No one could have known that I was in transition, the final stages of labor where the contractions get even more intense, when the cervix finishes dilation and the baby begins moving down the birth canal. Everyone had only just arrived, and no one had examined me. Someone said “breathe” and I tried to breathe. They said “breathe” and I breathed again. The baby was close and now I knew it. Someone was saying “push” and I was pushing. It was all wrong. But I listened to them. Push. Push. Push.

The old granny was sitting in a chair across the room, not saying a word. I could feel her trying not to look at me. She wanted to go lie down somewhere. I was sunk under the weight of an ocean full of water and the weight of the fact that no one could help me.

Now I was lying down, and Mose, kneeling between my raised knees, was the first to see the very top of the baby’s head. Soon the baby’s head was out, turned upward. “You’re almost done,” Mose said. The granny midwife sat solidly in her Adirondack chair.

I heard Mose say that something was wrong. I struggled upward. The baby’s face, its whole head, was covered with a grotesque, translucent layer of skin, so that it couldn’t breathe or open its mouth.

I heard someone say, “It’s the sac!” I fell back.

It’s the caul, I thought. He’s under the caul.

“Just pinch it and tear it off,” said the midwife.

I heard a cry, my baby’s cry, my baby’s first cry. My baby cried.

Then I felt a wet thing skittering out all little legs and arms. Everything was happening quickly.

“It’s born,” Mose said. I lifted myself on my elbows. I could see in the dimness a baby. It looked like a regular baby, except it was deep red. People were hovering above it. There was also a lot of blood.

“Rest,” Charity said. “Your baby is here. Rest.”

Somebody was handing Mose string and scissors from our kit, and the midwife was telling him where to cut, and I heard the metal grind of blades. I raised myself up and somebody said, “Everything’s fine, they’re cutting the cord.”

“Hand it to me,” I heard the midwife say. She sounded happy and cheerful now. “Let’s get it clean and warm.”

“What is it?” I whispered foggily. I had been waiting a long time. I lifted myself.

Charity tugged at me. “Lie still,” she said. “The placenta has to come out.”

“Hand him to me,” the midwife said.

“Let me hold him,” I said.

“Put him here on this towel, and we’ll clean him up,” the midwife said.

Mose handed the baby to the granny midwife and she wrapped him in a towel.

“What is it?”

“It’s a boy,” Mose said, from the other side of creation.

“My baby,” I started to moan. “My baby.”

“It’ll be only a couple minutes,” Mose said, “and you can have him.”

“I want my baby.” I was getting louder.

“Wait just a minute,” the midwife replied, impatient. “We’re cleaning him up for you. We’ll give him to you in a minute.” She had no tenderness, a fact I can actually understand but not support.

I could not help myself. I had never felt so much like an animal. “Give me my baby. Now,” I growled it. I would have leapt off the bed, and everyone in the room knew that.

“Take him, then,” the midwife said, resigned.

Mose came toward me with a bundle, and he laid it on my belly, between my swollen breasts. I unwrapped the towel and nestled my sweet baby against my skin, then covered both of us with the towel. I could feel his slipperiness. I could feel his smooth skin, new to air. I could feel little movements he made.

His eyes were open and he lay there against my heart, breathing air for the first time ever. He had come from the ocean to lay in my arms. I brought him back from the ocean. I touched his face covered in a whitish slime like some mushrooms I’ve seen. He had a lot of hair for a newborn, raven-colored. I touched it. I could smell an odd sweetness that was the inside of me, which had made him.

He would become the kindest person I’ve ever known. He would be filled with soul. He and I would share a remarkable and consuming bond. We would weather hardships and share an abundance of joy and goodness. We would remain lifelong (so far) friends and confidantes. All that was to come.

In the moment I looked at Mose and he looked at me, and maybe for the only time ever in our entire short life together we smiled at each other.

“He’s here,” I said.

The atmosphere changed. Stuart came from the kitchen. “2:14,” he said. “Exactly 2:14 a.m. I called time.” My neighbor Stuart was a strong man who’d help anybody in need. “You did it,” he said to me. He was beaming. “Congratulations.” He was the first one to say that, and I was proud then.

Arne came over and put his hand gently on my head. He’d been sitting in a corner worrying, trying to keep out of the way. I lay there holding my sweet baby.

When the placenta came out the midwife finally got her turn with the baby. She had delivered hundreds, and he would be her last. She was a nice person, it turned out. We just had cultural differences that we hadn’t foreseen. When Mose passed him back to me the baby—who for the next six weeks we would call Maka while we searched for his true name—was dressed in a flannel gown, swaddled in a small blanket, wearing a red cotton hat on his dark head. His eyes were wide open.

After that, people started to leave.

Later, when everyone had gone, back to their own beds to dream away what was left of the bruised night, three of us lay on the futon, like creatures made of petals, wordless, seized with wonder, hoping to heal, fragile to the touch.

THE END

Please do consider signing up for the birth story workshop, if you have been so lucky to give birth or attend a birth. I know you have a story, and there are very few places to put these powerful stories. Get it out of the tissues of your body and onto the page. I’ll help you.

So powerfully moving. I will do all I can to move a commitment and attend this workshop.

Beautiful