If you search online for Frances Lee Turner, you will find almost nothing about her. She was unknown to me until recently; and again I am driven to madness thinking of the women lost to history.

A year ago a stranger contacted me via my website to say that he had watched the documentary “Longleaf: The Heart of Pine,” produced by Rex Jones of the Southern Documentary Project. (I hope you watch it if you haven’t.) The man was Brad Ansley, a boatbuilder who lives outside Knoxville.

“I’m ashamed to say the wonderful documentary was the first I’d heard of you,” he said. I “immediately ordered Ecology of a Cracker Childhood.”

A few months later he wrote again. “I want to share a painting with you that my grandmother, Frances Lee Turner, painted probably back in the 20s or 30s. She was a great artist and well known at the time. My cousin in Arlington, Ga. just sent me this photo and I immediately thought of you. FLT traveled a lot and made paintings of the Deep South but also of California when she taught there during the Depression.”

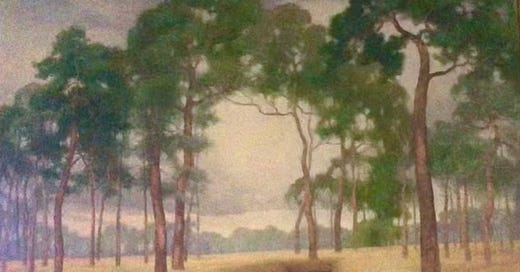

The impressionist painting he attached was of a blackwater creek running through a longleaf-wiregrass forest.

A pine flatwoods painted by Frances Lee Turner.

Not long after that email exchange, the Georgia Museum of Art asked me to give a lecture, “The Art of a Place Called Longleaf,” which I did on Thursday of this week. While I was researching for the talk, I thought of Turner.

*~*

Frances Hopkins Lee Turner was born on November 6, 1875 in Bridgeport, Alabama, in the far northeastern area of the state, to Mildred and Dr. Elisha Lee, a physician.

She attended the Centenary Female College in Cleveland, Tennessee and studied painting at the Corcoran Art School. She worked with the Student Art League in New York. She spent two summers painting with Will H. Stevens at the Newcomb School of Art, studied under Rhoda Holmes Nichols and Kenyon Cox at the Chester Spring Art School in Pennsylvania, and studied with Millard Sheets in California.

On Christmas Eve 1902 Frances Hopkins Lee married Dr. E.K. Turner, who was a professor of Latin at Emory. They had seven children.

In 1934 her New Deal painting of Bulloch Hall, the antebellum home of Teddy Roosevelt’s mother, Mittie, (located in Roswell, Ga.) was purchased by F.D. Roosevelt to hang in the White House. It’s now in the Smithsonian Collections. When she got the announcement, she was back home in Alabama with her 95-year-old father, since her mother had died the week before.

And that’s all I can find about her.

Yesterday Mr. Ansley sent me an image of a second painting by his grandmother, this one of a Florida spring. I am still trying to regain my composure.

One of Florida’s first-magnitude springs, painted by Frances Lee Turner.

From the Talk: Thinking about Place-based Art

Art as Response—Some of us are born in a landscape and we start to see it. Some of us respond to a landscape that is new to us. Often this is scenic.

Art as Culture—“Culture” is a collective narrative that explains life in a place—behaviors, symbols, beliefs, survival mechanisms—and this narrative is passed between inhabitants, geographies, and generations. Here the cave paintings made 30,000 years ago in France come to mind.

Art as Natural History—I’m thinking here of the botanical and faunal illustrations of Catesby, Audubon, Bartram, and so many others.

Art as Engagement—This is an expression of our life in and passion for a place.

Art as Warning—This would be Environmental Art, Eco-art, Land Art, and Place-based Art, which are ecologically and politically motivated. (When I was a young writer, I was told that the best writing had no hidden message, no mission. That was 100 percent wrong. All good art has a message. The more dire the circumstances, the more obvious the message, until we have works of art shouting at us.)

Art as Holy Text—There is something else happening in a piece of great art, and it has nothing to do with technique or subject. It has everything to do with spirit. You can see the spirit moving in a painting, because something beyond the painting is speaking to us. Sometimes it’s the earth speaking. It is lonely without us. We’re lonely without it. We belong to it. It belongs to us.

After the lecture I stood talking with the great landscape painter Philip Juras, who lives in Athens, and his partner, the artist Beth Gavrilles. We were talking about how hard it is to hie ourselves to our easels and desks. There is a reason why. Being fully present for spirit, which is multi-dimensional, to move through you, then onto a piece of 2-dimensional paper or canvas, is hard work. Checking email is lots easier and more fun.

However, if we pay enough attention and listen enough and feel deeply enough and concentrate enough and show up at our desks and easels and enter a liminal space that I write about a lot, our work will call out from this other plane.

Weymouth Woods, NC

From the Talk: Thinking about Place

I have had a lifelong preoccupation with place, which is why I am nostalgic for a place I’ve never even seen, my ancestral homeland of Great Britain, especially Scotland; and also why I returned to live in a place (the south of Georgia) that full of tensions—love and hate, violence and peace, and other complications that send people away, never to return. It’s a place that’s both beautiful and diminished. It’s full of life and full of grief. It destroys people, it nurtures people. Its people don't care and yet they do.

I’ve been trying to define “place” and “sense of place” for decades. Here are some definitions of place I’ve considered:

1. Place is property, land we own, my place.

2. Place is setting—backdrop, background, greenscreen.

3. Place is an ecosystem within ecosystems.

4. “A place is nothing more than a space with a story,” said John Tallmadge, a scholar of nature writing, “and the essential question is, ‘What happened here?’”

5. “A place is not a place until people have been born in it, died in it,” said Stegner. His definition of place is human experience on a piece of land.

6. A place is a piece of the whole environment that has been claimed by feelings, wrote Richard Wilbur.

7. Place is the intersection of the human heart with the natural world. That was me, the best definition I could come up with.

8. A place is a scenario, wrote Stephen Harrod Buhner in Earth Grief: The Journey into and through Ecological Loss. “We humans, like all living things, have been expressed out of this ever-moving, ever-changing scenario that we call Earth. We are irremovably, inextricably embedded within that scenario.”

I recently read this definition of place, and of everything I’ve read or thought about, this one makes the most sense to me. Honestly I’m ashamed that I didn’t figure this out on my own. Buckminster Fuller said, “Earth is a verb, not a noun.”

I think also that it’s important to emphasize that the expression is more than ecological and natural processes, more than evolution, more than natural history. We live in a multi-verse, and the Earth’s expression includes processes that would not appear in an ecology text. It includes emotions, for example. It includes gut feelings. It includes all the ways spirit moves.

Longleaf is a verb, not a noun.

An Ekphrastic Poem

This is a response to Kristin Leachman’s exhibit “Longleaf Lines,” now at the Georgia Museum of Art. Her paintings are of old-growth pine bark up close, depicted in earth tones, which are also skin tones—ivory, brown, gray, clay, tan, black.

That is my skin, she said.

I like it when you touch me.

I like it when you lean against me.

Sorry if I’m rough.

Thank you for coming.

I could not come to you,

not in the way of branches and needles.

But you came to me. Thank you.

I love my life here, all this sky, all my family,

the animals.

I’m connected to everything

and there’s always something happening,

some fox squirrel or pine snake.

It’s nice.

I’m grateful to be alive.

But let’s don’t think about that.

Let’s be in the moment.

This moment.

Yes.

When you put your hands on me like this,

against my back,

I shiver.

Do you feel me shivering?

I feel you shiver.

Just one thing:

I do worry about you.

I know I shouldn’t.

And you shouldn’t worry

about me.

We’ll be all right.

I just keep breathing.

You do the same.

Engage with the World through Language

Want to try your hand at an ekphrastic poem? You can use either of Frances Lee Turner’s paintings, above. What are the painting’s details? What memory or thought does it job? Does it remind you of something else? How does it feel? What does it say to you? Study the painting for a few minutes, then set your cell phone for 4 minutes and start writing.

If you’d be willing to share your work, you can do so at #writingwithjanisse or post to your social media & tag me, @tracklesswild or @janisseray.

Send Your Poems

My friend Peter Peteet of Decatur, Ga. and I have begun working on a collection of poems about the longleaf pine flat woods. The subject of each poem will be a species of plant or animal tied to the ecosystem. For example, we are interested in a poem about the red-cockaded woodpecker or about the gopher tortoise or about Harper’s beauty, and so on. This is the first announcement of the project. If you are a poet or writer and would like to receive our invitation to contribute, please make a comment or otherwise be in touch.

Longleaf Pine Shortbread

There’s so much more I’d like to say to you, but we have plenty of time for everything, later. Since this newsletter has been about longleaf, I’ll drop in a recipe for a shortbread cookie. It can be made with your evergreen conifer of choice.

1/4-1/2 cup fresh conifer needles (or rosemary)

1 cup unsalted butter (plant butter or coconut oil, if you’re vegan)

1/2 cup granulated (or coconut) sugar

2 tsp. satsuma (orange) zest

pinch of salt

2 cups all-purpose flour (if you’re gluten-free, I’m not sure what to tell you to do)

Finely chop the pine needles using a food processor, coffee grinder, spice grinder, or a knife if you are sure to chop very finely. Remove any large fibers or stray needles.

In a large (non-plastic) bowl, combine the pine, butter, sugar, zest, and salt. Mix until creamy.

Gradually add flower until you have a ball of buttery dough.

Divide the dough into 2 piles on sheets of parchment paper. Using the paper as an aid, roll each pile into a log about 1.5 inches in diameter. Wrap and freeze for 15 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 350.

Unwrap dough and cut into 1/4-inch-thick cookies. Place 1 inch apart on parchment-lined baking sheets. Bake about 10 minutes, until the edges are golden brown.

Abandoned Wren Nest

I’m going to leave you with a photo of a nest constructed by a Carolina wren in a cow skull reminiscent of Georgia O’Keefe. It hangs on our porch. The nest, a fine example of the art of place, was abandoned as the weather finally began to turn cold.

I’m so interested in your section that defines place. My research is focused on place writing and I really appreciate your open mindedness on the subject. You might like to subscribe to my Place Writing Substack. Signing up to yours now!

Janisse, This is Anne Green in Savannah. I last saw you at The Learning Center in September 2021. Before that it was at the Looking Glass Rock Writers' Conference in Brevard. I would like an invitation to submit to the long leaf pine collection. awwestbrook@bellsouth.net